Introduction

Sir Isaiah Berlin (1909–1997) was a Russian‑British historian of ideas and political theorist whose lucid essays revived Anglophone political philosophy and anchored modern liberal thought in a distinctive defense of freedom and value pluralism. Best known for the essay “Two Concepts of Liberty,” he drew a seminal distinction between negative liberty—freedom from coercion—and positive liberty—self‑mastery or freedom to pursue chosen ends—warning that monistic, perfectionist readings of the latter can enable paternalism and totalizing politics that erode individual freedom.

Across studies of Enlightenment critics, Romanticism, and historicism, Berlin argued that fundamental human values are many, real, and often in conflict, requiring trade‑offs without a single, overriding hierarchy—a pluralism he sharply contrasted with ideological systems that promise harmonious unity at the cost of coercion. Knighted in 1957 and later appointed to the Order of Merit, Berlin’s influence endures through a humane, anti‑authoritarian liberalism skeptical of determinism and fanaticism, and through an engaging body of lectures and essays that made complex ideas accessible without sacrificing depth.

Below is a structured and detailed explanation with key points, examples, and illustrations to understand Sir Isaiah Berlin’s Political Thought

1. Context and Background

- Isaiah Berlin (1909–1997) was a British political philosopher, historian of ideas, and essayist.

- He was deeply influenced by liberalism, Romanticism, and the catastrophes of the 20th century — fascism, communism, and totalitarianism.

- His work is not systematic philosophy but rather a set of insightful essays exploring the nature of freedom, value, and moral conflict.

- Major works:

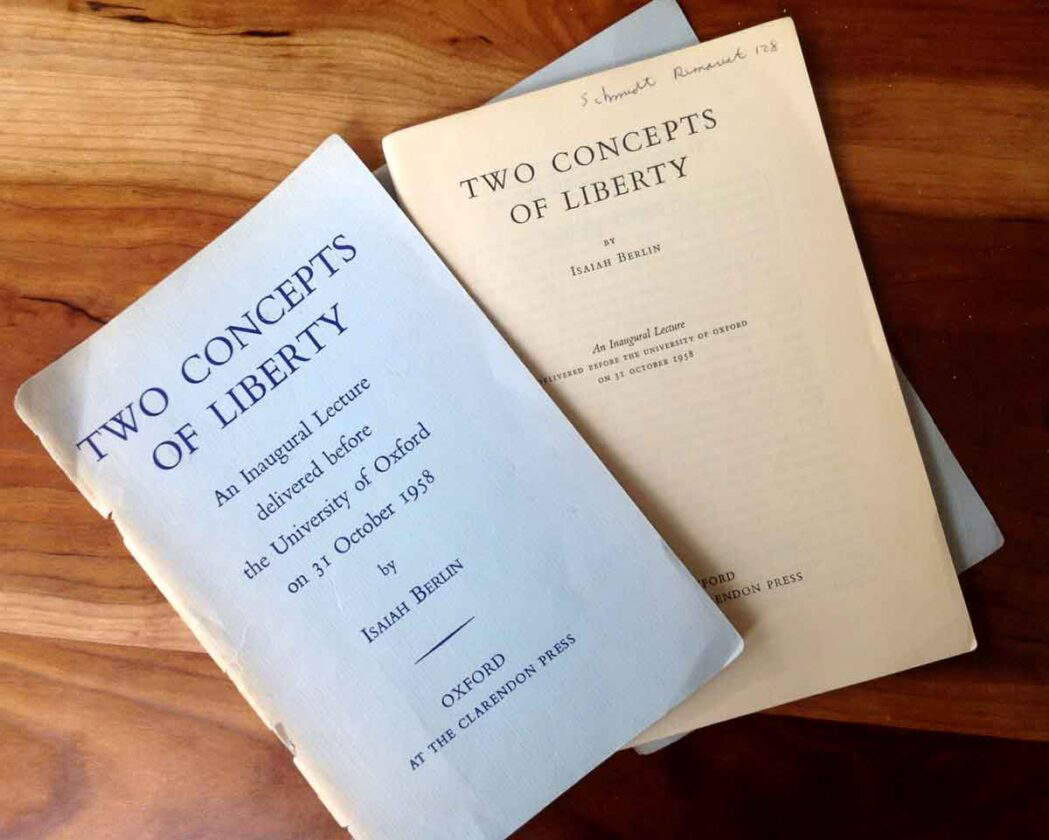

- Two Concepts of Liberty (1958)

- The Hedgehog and the Fox (1953)

- Four Essays on Liberty (1969)

- The Crooked Timber of Humanity (1990)

2. The Central Theme: Liberty

Berlin’s most famous contribution is his distinction between Two Concepts of Liberty — negative liberty and positive liberty.

(A) Negative Liberty – “Freedom From”

Definition:

Negative liberty is freedom from interference — the area within which an individual can act without being obstructed by others.

“I am free to the degree to which no one interferes with my activity.” — Berlin

Example:

- A citizen in a liberal democracy can express opinions, choose their career, practice religion, or refuse to do something — without coercion by the state or others.

- Freedom of speech, property rights, and protection from arbitrary arrest are negative freedoms.

Illustration:

If the government does not censor your newspaper, you are free to publish what you like.

But if it dictates what you can or cannot write — your negative liberty is violated.

Philosophical roots:

- John Locke, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Hobbes.

- It is the foundation of classical liberalism and modern Western democracies.

(B) Positive Liberty – “Freedom To”

Definition:

Positive liberty is the freedom to be one’s own master — the ability to control one’s own life and realize one’s true self.

“I wish to be a subject, not an object — to be moved by reasons, not by causes.”

Example:

- Education that enables one to think critically.

- Laws that protect citizens from poverty or ignorance, allowing them to act autonomously.

Illustration:

A person who is addicted, poor, or uneducated may be formally free (no one stops them from acting), but not truly free because they lack the ability to make meaningful choices.

Philosophical roots:

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, G.W.F. Hegel, Karl Marx.

- Associated with self-realization and collective will.

Berlin’s Warning About Positive Liberty

Berlin warned that positive liberty can become dangerous when interpreted collectively — i.e., when someone claims to know what others’ “true selves” or “true interests” are.

Example:

- Rousseau’s “general will” or Marx’s “class consciousness” can be used to justify authoritarianism.

- Leaders may claim: “We will force you to be free” — suppressing individual dissent in the name of collective liberation.

Historical illustration:

- In the Soviet Union, Stalin claimed to liberate workers from oppression — but this justification led to totalitarian control and mass repression.

- Thus, positive liberty can easily slip into tyranny if not balanced with negative liberty.

3. Value Pluralism

Another central pillar of Berlin’s thought is value pluralism — the belief that human values are many, conflicting, and incommensurable.

Core idea:

- There is no single, universal moral truth that can reconcile all human values.

- Values like liberty, equality, justice, happiness, order, and love are all good — but they often conflict and cannot all be maximized at once.

“The necessity of choosing between absolute claims is part of the tragedy of the human condition.” — Berlin

Example:

- A society valuing absolute equality may have to restrict liberty (e.g., high taxation, redistribution).

- A society prioritizing liberty may tolerate inequality.

Illustration:

A mother might value both honesty and kindness, but sometimes she must lie to spare a child’s feelings. Both are good, but they clash — and no universal rule can solve the conflict.

Philosophical implication:

- Berlin rejected both moral relativism (that all values are equal) and moral monism (that one value can rule them all).

- He embraced a tragic liberalism — recognizing that human life involves real, painful choices between equally valid goods.

4. Anti-Utopianism

Because values conflict, Berlin argued that any attempt to create a perfect, harmonious society is dangerous.

“The pursuit of the ideal has often led to the slaughter of innocents on the altars of great historical ideals.”

Examples:

- Totalitarian ideologies like Nazism or Communism claimed to possess the final truth — and justified massive repression in pursuit of a perfect world.

- Berlin saw liberalism as the only political system humble enough to accept imperfect coexistence rather than utopian perfection.

5. The Hedgehog and the Fox

In this essay (1953), Berlin used a metaphor from the Greek poet Archilochus:

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Interpretation:

- Hedgehogs: Thinkers who interpret the world through one central vision or principle (e.g., Plato, Marx, Nietzsche).

- Foxes: Thinkers who pursue many ideas, accept complexity and contradictions (e.g., Shakespeare, Aristotle, Goethe, Tolstoy).

Berlin’s preference:

He admired the fox — pluralistic, flexible, and skeptical of all-encompassing ideologies. This fits his liberal pluralism — valuing diversity, open debate, and compromise.

6. Liberalism as a Political Ethic

Berlin’s liberalism is not based on an abstract ideal but on a moral disposition:

- Tolerance of difference

- Awareness of human fallibility

- Commitment to protecting individual choices

- Recognition that conflict is inevitable, and the role of politics is to manage it peacefully.

Example:

A liberal society should allow:

- Artists to express dissent

- Minorities to preserve their culture

- Citizens to make mistakes — as long as they do not harm others.

7. Influence and Legacy

- Inspired later liberal thinkers like John Gray, Charles Taylor, and Joseph Raz.

- Influenced debates about multiculturalism, human rights, and democratic pluralism.

- Berlin’s realism about moral conflict remains vital in an age of political polarization.

8. Summary Table

| Concept | Definition | Example | Berlin’s Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Liberty | Freedom from interference | Free speech | Threatened by coercive states |

| Positive Liberty | Freedom to realize oneself | Education, empowerment | Can justify authoritarianism |

| Value Pluralism | Many genuine but conflicting values | Liberty vs. Equality | No single “true” solution |

| Anti-Utopianism | Rejection of perfect societies | Communism, Nazism | Leads to tyranny |

| Liberalism | Tolerance, individual rights | Democratic pluralism | Best framework for coexistence |

Conclusion

Isaiah Berlin teaches that:

- Human freedom has two faces — both valuable, but one (positive liberty) can turn dark.

- Human values are plural and conflicting, and no single ideology can reconcile them.

- Politics must aim not for perfection, but for balance, tolerance, and humane compromise.

Examination Zone

In this part, we will discuss the kinds of questions that may help you in the preparation of examination.

- Explain the political thought of Sir Isaiah Berlin – 15 Marks

- Write a note on negative liberty according to Sir Isaiah Berlin – 10 Marks

- Explain positive liberty according to Sir Isaiah Berlin – 10 Marks

How to answer these questions.

1. Explain the political thought of Sir Isaiah Berlin

Summaries the above points in a concise form with examples.

2. Write a note on negative liberty according to Sir Isaiah Berlin

Definition: Negative liberty means the absence of external interference — a condition where an individual can act as he wishes, without being obstructed or controlled by others, especially by the state or society. Isaiah Berlin said “I am free to the degree to which no man or body of men interferes with my activity.”

Berlin’s idea of negative liberty is central to classical liberal thought, emphasizing individual freedom, limited government, and personal autonomy.

Important features of negative liberty

Absence of External Interference: The most fundamental feature of negative liberty is that it defines freedom as “freedom from interference” by others. A person is free when no external agent — whether the government, society, or another individual — obstructs their actions. It is not about having power or resources to act, but about not being stopped from acting as one chooses.

Example: If the government does not prevent you from expressing your opinion, joining an association, or choosing your occupation, you enjoy negative liberty. If, however, censorship or social pressure restricts your choice, your liberty is reduced.

Illustration: Imagine a journalist allowed to write freely without government censorship — that’s negative liberty in practice.

The Existence of a Private Sphere: Berlin emphasized that negative liberty requires a protected area or private domain within which individuals are free to act without interference. Every individual should have a minimum personal space — a domain of life (beliefs, speech, lifestyle, religion, property) that the state or others must not invade. This “private sphere” is essential for individual dignity, creativity, and self-expression. Berlin believed that protecting this sphere of non-interference ensures a pluralistic society — one that allows diverse ways of life to coexist peacefully.

Example: Freedom to choose one’s religion, personal relationships, or profession should lie outside state control. If the state dictates these choices, liberty is lost.

Limited Role of the State: In the concept of negative liberty, the state’s role must be minimal. The government should not aim to make people moral, happy, or rational — its role is only to protect individuals from harm and coercion. The state should prevent others from interfering, not direct citizens toward a particular “good life.” Over-regulation or paternalism reduces individual freedom.

Example: Laws that prevent theft, assault, or fraud protect freedom, but laws forcing people to follow a particular religion or ideology destroy it.

Quantitative and Relational Nature of Freedom: Negative liberty can be measured in degrees — the more extensive the area in which an individual is left alone, the greater their freedom. It is quantitative because liberty increases or decreases depending on how large or small the sphere of non-interference is. It is also relational, because freedom always refers to freedom from someone — from the coercion of other individuals or institutions.

Example: A citizen in a liberal democracy has more freedom than one in an authoritarian regime because the area of non-interference is larger.

A person imprisoned unjustly has less negative liberty because others are directly interfering with their choices. Thus, liberty is not absolute but relative — it depends on how much control others have over your actions.

Compatibility with Value Pluralism and Individual Diversity: Negative liberty supports the idea that people have different goals, values, and life plans, and each should be free to pursue them in their own way, as long as they do not harm others. It accepts pluralism — that there are many legitimate ways to live a good life. The state should not impose one moral or ideological standard on everyone.

Example: In a liberal society, some people may choose religious life, others artistic or scientific pursuits — all have equal freedom as long as no one coerces another. Berlin believed that respecting negative liberty preserves diversity, tolerance, and peaceful coexistence in society. It allows people to follow their own beliefs without fear of punishment or social persecution.

Conclusion: In summary, negative liberty according to Isaiah Berlin is, Freedom from external interference, guaranteed by a limited state, Existing within a protected private sphere, quantitatively variable and relational, Supportive of individual diversity and pluralism. Berlin viewed this concept as the foundation of liberal democracy, emphasizing tolerance, limited government, and respect for personal choice. He warned that attempts to impose a single idea of the “good life” — as seen in positive liberty — often lead to authoritarianism.

3.Explain positive liberty according to Sir Isaiah Berlin

Introduction: Important features of positive liberty according to Sir Isaiah Berlin, as presented in his classic essay “Two Concepts of Liberty” (1958).

Berlin’s distinction between negative and positive liberty is central to his political thought. While negative liberty means freedom from external interference, positive liberty means freedom to control one’s own life — to be one’s own master.

Positive Liberty Meaning: “I wish to be a subject, not an object — to be moved by reasons, by conscious purposes which are my own, not by causes which affect me from outside.” — Isaiah Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty”

Positive liberty is the idea of being free to determine and direct one’s own life according to one’s rational will, not merely being left alone. It is about self-mastery, self-realization, and autonomy — the capacity to act as your own master rather than being ruled by external forces or irrational impulses.

Important Features of Positive Liberty

1. Freedom as Self-Mastery: Positive liberty means being one’s own master — having control over one’s decisions, emotions, and actions. It is not merely doing what one desires at the moment, but acting rationally according to one’s true or higher self.Berlin traces this idea to thinkers like Plato, Rousseau, and Kant, who saw true freedom as obedience to reason rather than to impulse or passion.

Example: A person addicted to drugs may act on their desires but is not truly free, because they are enslaved by their addiction. A person who acts rationally and with discipline, choosing what is genuinely good for them, demonstrates positive liberty.

2. Freedom to Realize One’s True Self: Positive liberty involves the idea of self-realization — the development of one’s full potential as a rational, moral being. Berlin points out that in this view, every human being has a “true self” that can be discovered and cultivated through reason and moral awareness. To be free, one must live according to this authentic or rational self, not the lower, impulsive self driven by desires and fears.

Example: Education, self-discipline, and moral development help individuals become truly free, because they enable people to act according to their higher understanding rather than mere impulses.A student who disciplines herself to study rather than give in to distraction exercises positive liberty, because she acts in line with her long-term, rational goals.

3. Collective or Participatory Aspect of Freedom: Positive liberty can take on a collective dimension — freedom as participation in self-government or in the general will of the community. Thinkers like Rousseau and Hegel argued that individuals realize their freedom not in isolation but by being part of a rational, moral community. By participating in collective decision-making, citizens share in determining the laws that govern them — thus becoming co-authors of their political life.

Example: When citizens vote, engage in democratic debate, or obey laws they have helped create, they are positively free, because they obey themselves through the collective will. Berlin recognized this as an inspiring but risky idea — it can easily be distorted into authoritarianism if rulers claim to represent the “true will” of the people

4. The Role of Reason and Autonomy: Positive liberty assumes that true freedom lies in acting rationally and autonomously, not under the compulsion of passion, ignorance, or external forces. For Berlin, positive liberty has strong links with Enlightenment rationalism. To be free is to use one’s reason to choose what is best, to make informed and deliberate choices rather than being a slave to circumstance or emotion.

Example: An uneducated person might be legally free (negative liberty) but unable to make informed choices. Education and moral reasoning increase positive liberty by enabling autonomy. A person who understands their rights, critically evaluates options, and decides independently acts with positive freedom — they are guided by understanding, not manipulation or ignorance.

5. The Potential Danger of Positive Liberty: Berlin’s most famous insight is that positive liberty can be misused — it can justify coercion in the name of “true freedom.” If rulers claim that they know what individuals’ “true interests” are, they may force people to obey — claiming that this coercion actually makes them free. “I may be coerced into being free… they must be forced to be free.” — Rousseau (criticized by Berlin) This transforms a noble idea (self-mastery) into a tool of oppression, because: The “true self” is defined by someone else (the state, the party, or an ideology). Individuals are denied their right to make their own choices, even mistaken ones.

Examples: Communist regimes claiming to “liberate” workers by controlling all aspects of life. Fascist movements claiming to “free” the nation by suppressing dissent. Berlin’s conclusion: Positive liberty is valuable but must be limited and balanced with negative liberty, to prevent it from justifying tyranny.

Conclusion: In Isaiah Berlin’s view, positive liberty expresses a deep human aspiration — to live consciously, rationally, and in control of one’s destiny. However, Berlin warned that when interpreted collectively or paternalistically, it can justify coercion and totalitarian control.

Thus, while positive liberty reflects the moral dimension of freedom, it must be balanced with negative liberty — the protection of individuals from interference — to safeguard genuine human freedom.

For further readings refer these links:

- M Phil Thesis on Sir Isaiah Berlin’s thoughts.

- Isaiah Berlin, “TWO CONCEPTS OF LIBERTY,” Four Essays On Liberty, (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1969), p. 118-172.

- Examine Isaiah Berlin’s two concepts of Liberty. – Vidyaocean