Introduction

Plato, an eminent Greek philosopher born circa 427 BCE, is one of the most influential figures in Western philosophy. A student of Socrates and the teacher of Aristotle, Plato founded the Academy in Athens, one of the earliest institutions of higher learning in the Western world. His extensive writings, primarily in the form of dialogues, explore a wide range of subjects including ethics, politics, metaphysics, and epistemology. Through works like “The Republic,” “Phaedrus,” and “The Symposium,” Plato’s philosophical inquiries have profoundly shaped intellectual thought and continue to be pivotal in the study of philosophy and the humanities.

what is state according to plato

- An Organic Entity: Plato views the state as an organic entity, analogous to a living organism, where each part functions for the good of the whole. The health of the state depends on the proper functioning and harmony of its various parts.

- The Ideal State Reflects Justice: For Plato, the state is the embodiment of justice. Justice in the state mirrors justice in the individual, achieved when each class performs its designated role without overstepping its bounds.

- Three Classes: The state consists of three classes: rulers (philosopher-kings), auxiliaries (warriors), and producers (farmers, artisans, merchants). Each class contributes to the stability and functionality of the state.

- Philosopher-Kings as Rulers: The state is governed by philosopher-kings, who possess the knowledge and wisdom to make decisions for the benefit of all. Their rule is based on rational insight and understanding of the Forms, particularly the Form of the Good.

- Role of Education: Education is fundamental in shaping the ideal state. It ensures that each class is properly trained for its role. The philosopher-kings undergo extensive education to prepare them for governance.

- Communal Living Among Guardians: To prevent conflicts of interest, the guardians (rulers and auxiliaries) live communally, without private property or traditional family structures. This communal living ensures their loyalty to the state above personal interests.

- The Noble Lie: Plato introduces the concept of the “noble lie,” a myth perpetuated to maintain social harmony and justify the class structure, suggesting that people are born with different types of souls suited to different roles.

- Meritocracy: In Plato’s state, individuals are assigned roles based on their abilities and virtues rather than wealth or birthright. This meritocratic principle ensures that the most capable individuals occupy positions of responsibility.

- Function Over Freedom: Plato prioritizes the function and stability of the state over individual freedoms. Each person’s primary duty is to fulfill their role, contributing to the overall harmony and order of the state.

- Harmony and Unity: The state must achieve a harmonious balance where each class works together for the common good. Unity is essential, with the different classes cooperating and complementing each other’s functions to maintain a just and stable society.

Plato’s Theory of justice

Plato’s theory of justice, as articulated in his seminal work “The Republic,” posits that justice is a fundamental virtue both for individuals and the state. According to Plato, justice in the individual is a harmonious structure where each part of the soul—reason, spirit, and appetite—performs its appropriate function under the guidance of reason. This mirrors his vision of a just state, where society is divided into three classes: rulers (philosopher-kings), auxiliaries (warriors), and producers (workers). Each class must fulfill its specific role and cooperate for the overall harmony and stability of the state. Plato’s concept of justice is thus a blend of ethical and political dimensions, aiming to create a balanced and well-ordered society where everyone contributes to the common good according to their abilities and virtues.

- Harmony of the Soul: Plato’s theory of justice begins with the idea that justice in an individual is achieved when the three parts of the soul—reason, spirit, and appetite—are in harmony, with reason guiding the spirit and appetite.

- Tripartite Class Structure: Justice in the state mirrors justice in the individual, with society divided into three classes: rulers (philosopher-kings), auxiliaries (warriors), and producers (farmers, artisans, merchants). Each class must perform its designated role for the state to function justly.

- Role of Reason: In both the individual and the state, reason must govern. In the state, this is embodied by the philosopher-kings, whose wisdom and knowledge guide the other classes.

- Specialization: Justice involves each class and each individual performing the role for which they are naturally best suited, contributing to the overall good without overstepping their functions.

- The Allegory of the Metals: Plato’s “noble lie” suggests that people are born with different types of souls—gold for rulers, silver for auxiliaries, and bronze or iron for producers. This myth helps maintain social order and justifies the class structure.

- Education and Virtue: Justice is cultivated through a rigorous system of education that ensures rulers are wise and virtuous, warriors are courageous, and producers are temperate.

- Justice as the Highest Virtue: For Plato, justice is the highest virtue that integrates and balances the other virtues (wisdom, courage, and temperance) in both individuals and the state.

- Interdependence of Classes: Justice requires that each class in the state depends on the others, creating a cohesive and well-ordered society where each part supports the whole.

- Guardians’ Communal Living: To prevent corruption and conflicts of interest, the ruling and auxiliary classes live communally, without private property or traditional family ties, ensuring their focus remains on the common good.

- Justice as Functional Excellence: Ultimately, Plato’s justice is about functional excellence—each part of the soul and each class in society must perform its function well, contributing to the harmony and order that define a just individual and a just state.

philosopher king

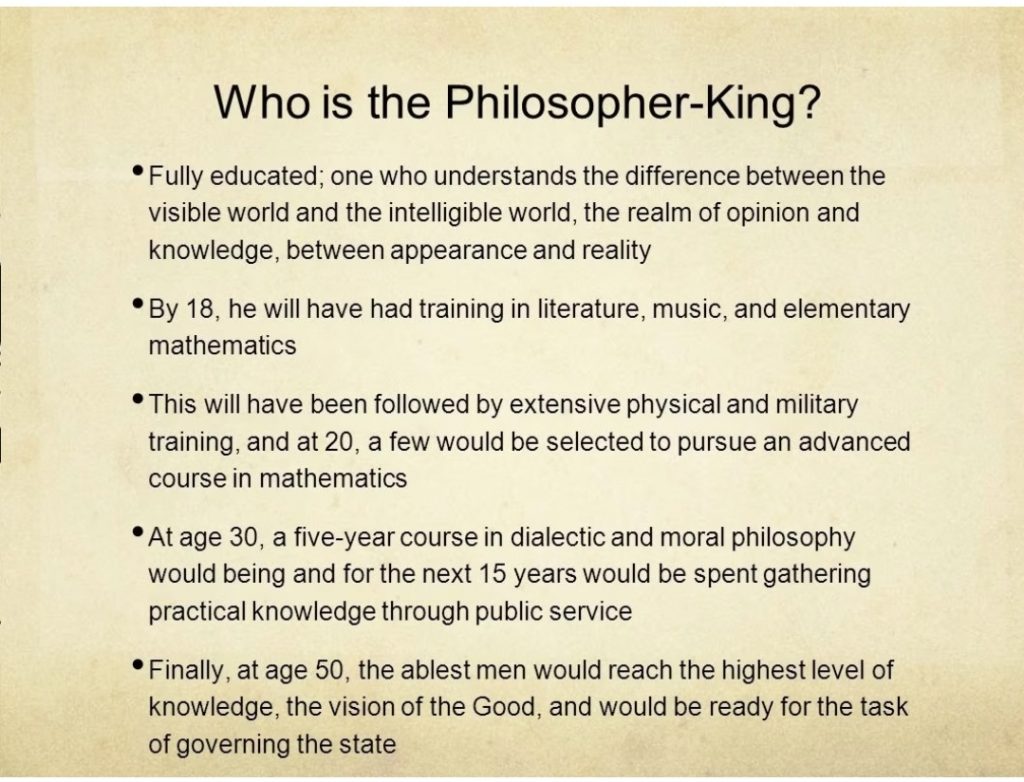

Plato’s concept of the philosopher-king, as detailed in “The Republic,” is a cornerstone of his vision for an ideal state. A philosopher-king is a ruler who combines the wisdom of a philosopher with the authority of a king, embodying both intellectual and moral virtues. Plato argues that only those who truly understand the Forms, especially the Form of the Good, are fit to govern. These enlightened rulers possess the knowledge necessary to create a just and harmonious society, as their decisions are guided by reason and the pursuit of the common good rather than personal interest or ambition. By advocating for philosopher-kings, Plato underscores the importance of wisdom and virtue in leadership, positing that a just society can only be achieved under the guidance of those who are best equipped to understand and implement the principles of justice.

- Philosopher-Kings as Ideal Rulers: Plato’s philosopher-kings are envisioned as the ideal rulers who possess both the wisdom of a philosopher and the authority of a king, ensuring that governance is based on knowledge and virtue.

- Knowledge of the Forms: Philosopher-kings have a deep understanding of the Forms, especially the Form of the Good, which enables them to make informed and just decisions that benefit the entire society.

- Rigorous Education: The path to becoming a philosopher-king involves a rigorous education system that includes training in mathematics, dialectics, and philosophy, aimed at developing both intellectual and moral excellence.

- Rule by Wisdom: Unlike ordinary rulers who may be driven by personal interests or desires, philosopher-kings rule by wisdom, guided by their understanding of ultimate truths and the common good.

- Guardians of Justice: As the guardians of justice, philosopher-kings ensure that each class in society performs its appropriate role, maintaining harmony and balance within the state.

- Lack of Personal Ambition: Philosopher-kings are characterized by their lack of personal ambition and desire for wealth or power. Their primary motivation is the well-being of the state and its citizens.

- Communal Living: To prevent corruption and ensure their loyalty to the state, philosopher-kings live communally with the auxiliary class, without private property or traditional family ties.

- Selection Based on Merit: Plato’s philosopher-kings are chosen based on their natural abilities and virtues, rather than birth or wealth, ensuring that only the most capable individuals govern.

- Reluctant Rulers: Ideally, philosopher-kings are reluctant rulers who govern out of a sense of duty rather than a desire for power, believing that their knowledge obligates them to lead for the greater good.

- Moral and Intellectual Exemplars: Philosopher-kings serve as moral and intellectual exemplars for the rest of society, embodying the virtues of wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice that Plato deems essential for a well-ordered state.